Speaker Bios

Carl Safina Carl Safina’s writing about the living world has won him a MacArthur “genius” prize; Pew, and Guggenheim Fellowships; book awards from Lannan, Orion, and…

Carl Safina Carl Safina’s writing about the living world has won him a MacArthur “genius” prize; Pew, and Guggenheim Fellowships; book awards from Lannan, Orion, and…

Each session lasts an hour and half, divided into three parts: * a half-hour presentation by the speaker; * a half-hour Q&A conducted by an invited…

Researchers are trying to grow human organs in pig embryos. But if the human stem cells start migrating around the embryo, the baby pig might start growing a human brain, too.

What would it be like to be eaten by a large predator? We humans are, after all, basically a prey species, and our drive to dominance is a product of human frailty.

They’re wealthy men of the old aristocracy, who believe in “Honoring God by Honoring His Creatures” — that is, by killing them.

A new book explains why we humans are so screwed up, and why we take it out on our fellow animals.

Last week, I happened upon the much-acclaimed TV series from the U.K. Dark Mirror – a kind of Twilight Zone for the 21st Century. In the…

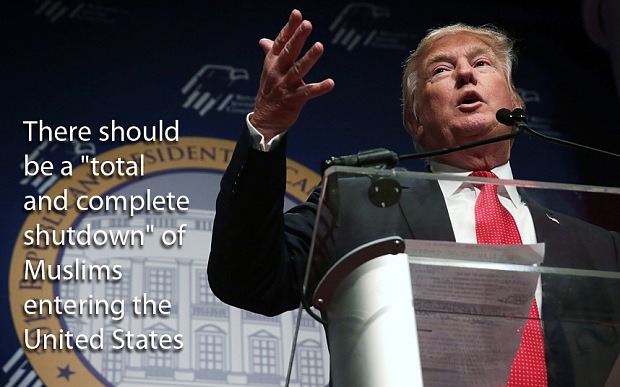

Along with panicky denunciations from the shocked-horrified-and-appalled Republican establishment, there was much cheering and applause from Donald Trump’s zombie supporters when he called for “a total…

Everybody loves a hero. And we all would like to be heroes. Heroism is something we humans strive for. Other kinds of animals behave heroically, too,…

A former soldier who served in Iraq, comes home to a nation in denial, droughts and floods, mass migrations, and an epidemic of anxiety and depression.

Last week, when zoo officials in Japan named a baby monkey Charlotte in honor of the newborn British princess, they set off a storm of protest.…

Part Six in the series “I Am Not an Animal.” In previous posts, we looked at how our anxiety over our mortal, animal nature drives us to distance ourselves, psychologically and literally, from our fellow animals; at how ancient mythologies told of a “fall” from a time when we were in harmony with the other animals; and at how our belief in “human exceptionalism” has led us to treat them.

Now we ask: Where do we go from here, and is there any way out of our situation?

(Fifth in a series about how and why our relationship to our fellow animals has deteriorated to the point of an unfolding mass extinction.)

(Fifth in a series about how and why our relationship to our fellow animals has deteriorated to the point of an unfolding mass extinction.)

By Dr. Lori Marino

However much we like to think of ourselves as different from and superior to the other animals, we can’t escape the fact that we are, just like them, mortal, physical creatures, equally subject to the laws of nature.

The existential terror that’s caused by this ever-present knowledge has been studied at length by psychologists in the field of Terror Management Theory (TMT).

In previous posts we’ve talked about how our relationship to our fellow animals and the way we treat them is driven by our anxiety over the fact that we’re animals, too, and our denial of our own animal nature.

In his book Immortality: The Quest to Live Forever and How it Drives Civilization, Stephen Cave discusses the chief ways in which we persuade ourselves that we’re not really animals, that we can avoid death altogether, or at least that some part of us will live on in some way after we’re dead. Here’s the trailer to the book:

In the first of two posts, Cave explains how, once we decide that we are fundamentally different in kind from other animals, we can then view them as having a lower moral status. And that, in turn, opens up "a whole world of possibilities for how we treat them."

Starting around 9,000 years ago, the agricultural era brought about the large-scale domestication of animals and a fundamental shift in our relationship to them. Less and less beings of great mystery and power, they were becoming, instead, commodities.

(Fourth in a series about how and why our relationship to our fellow animals has deteriorated to the point of an unfolding mass extinction.)

How and when did we humans decide we didn’t want to think of ourselves as animals any longer? How did we go from thinking of the other animals as essentially our equals to treating them as commodities that exist to be mined from the oceans by huge factory ships and manufactured from birth to death on factory farms?

It’s obviously a long and complex story, but we can get an idea of how it took place over thousands of years in various parts of the world.

(Third in a series about how and why our relationship to our fellow animals has deteriorated to the point of an unfolding mass extinction.)

In the story of the Garden of Eden, our early ancestors find themselves confronted by a choice.

They’re already developing an increasingly complex self-awareness that gives them the ability to think in terms of good and bad. And they’re acquiring an existential understanding of their personal mortality.

As this awareness grows, they find themselves hearing two voices: one calling them back to a state of innocence in paradise; the other beckoning them forward to a future where they might become “as gods” in their own right, taking dominion over the world, freeing themselves from their animality, and even becoming immortal.

(Second in a series about how and why our relationship to our fellow animals has deteriorated to the point of an unfolding mass extinction.)

The psychology behind why we humans continue to reduce the other animals to the status of resources, commodities and property – even at risk of driving much of life on Earth to mass extinction.

The psychology behind why we humans continue to reduce the other animals to the status of resources, commodities and property – even at risk of driving much of life on Earth to mass extinction.

In the Ancient Greek drama Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, Prometheus tells of the terrible mistake he made in giving humans self-awareness and enlightenment. The “gift”, he…

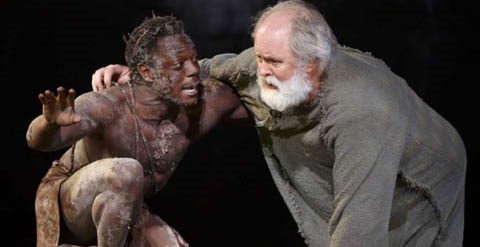

“The possibility of genuine chaos, real cannibalizing barbarism, is closer to the surface than we can possibly imagine.” Oscar Eustis, artistic director, New York’s Public Theater.